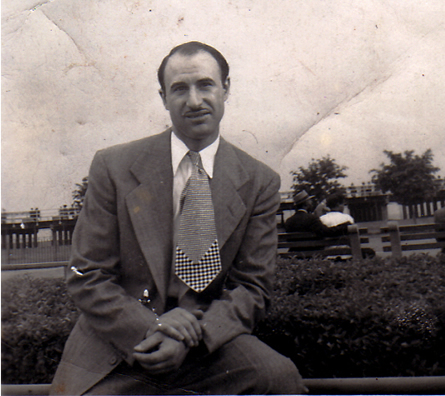

In the beginning, I was very much my father’s son. He was a self-made man; born in Sicily and arriving in New York City when he was only seven years old. He never completed high school but became the foreman of a successful factory and the right hand idea man of the owner, Mr. Chamberlain. He was as Italian as he was an American as he was a New Yorker. He was the guy the ladies swirled around at a party, he was the guy you asked where to go on the town, and he was the guy you asked for help when you needed a hand. He was Tony, the guy who was my father when I was growing up in Brooklyn; I was Anthony his son, and when I grew up I would become like my Dad and be called Tony.

**********

Daddy would often take me after mass on Sunday mornings to ride the rides at Coney Island while Mom stayed home with my brother and prepared a traditional Italian dinner that we always ate at one p.m. We were both still dressed in our Sunday suits but with our jackets carelessly flung across the back seat of his big black shiny sedan. I used to sit in the front warm vinyl seat close next to him, watching how he maneuvered the car, turning the big steering wheel with his muscled arms that bulged through the rolled-up sleeves of his crisply pressed white shirt. It was a short ride from our brownstone in Park Slope, but every excursion was an adventure with Dad as he listened to the radio and gave me his commentary on the politics of the day or the status of the Dodgers playing at Ebbets Field the previous night. He would flick his cigarette out the little side window and some of the ashes would blow on my face, which made me feel like Casey Jones, the engineer

My favorite ride, “Spook-A-Rama,” always managed to creep me out with its Grand Guignol tableaux. Of course my father didn’t help by adding his own grotesque noises in the dark as he startled me with a sudden poke in the ribs. He once took me up on the Parachute Drop, and as if I wasn’t scared enough he began to rock the carriage just as we were about to be released for our quick, rapid decent. He laughed all the way down as I held on to him for my life with my eyes closed to the very bone-rattling end. My second favorite ride was the train that circled a huge parking lot. I again pretended I was the engineer, my head sticking out over the side, the wind blowing though my hair, and when we came back into the station, my dad pulled me out of the train car and landed me on the ground with a good-natured thump and chortle. He always bought me a hot dog at Nathans as he downed a dozen clams-on-the-half-shell. He made a big deal about us not telling my mother, who was home cooking. It was our little secret between us two guys. When we got home we made it through Mom’s manicotti, but we started to slow down with conspiratorial glee at the Leg of Lamb with roasted potatoes and string beans. My mom, who should have worked for the FBI, of course, knew everything as she meaningfully smiled as I helped her clear the dishes. We never had dessert until an hour or so later and besides my father never ate dessert. I made tea for mom and cut here a piece of Ebinger’s blackout cake. As she was blowing over the saucer to cool the tea down, she called me over to feel the slight kicking in her stomach of my new baby brother or sister. It was weird.

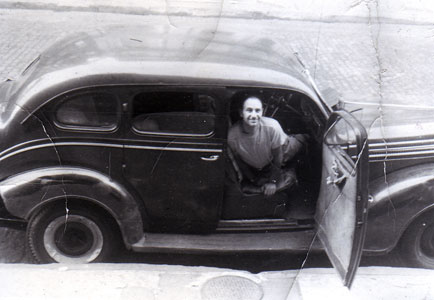

My Dad

One Saturday afternoon, The Avon Theatre on 9th Street was showing a double bill of the old Universal films: Dracula and Frankenstein. I loved horror movies but had never seen Frankenstein. My Dad was working that afternoon at Cel-U-Dex, his factory in downtown Brooklyn next to the Manhattan Bridge so he couldn’t take me to the movies. I asked my Mom if I could go, and after a moment’s hesitation, she gave me a quarter out of the coffee tin and told me to enjoy myself, be careful and not get the butter popcorn all over my new dungarees.

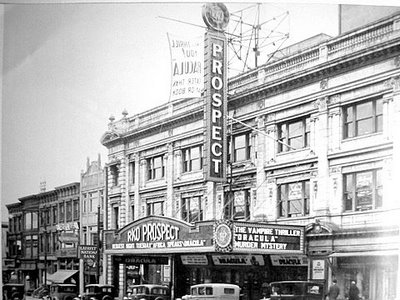

I bounded down the three landings of our tenement and out the door onto 10th Street into an overcast afternoon. I traced my usual trail that I took to go to school at St. Thomas Aquinas, past the drugstore on the corner of Sixth Avenue and down the steep slope of 9th Street past the dry cleaners, the YMCA, and the huge RKO Keith’s Prospect Theatre. The Avon Theater, next to the post office and Duffy’s Funeral Parlor, was a very small place showing second run movies. I got to the theatre just as it started to rain.

We were made to sit in the children’s section, where a matron dressed in white like a nurse would patrol up and down the aisles with a flashlight, shining it into our eyes if there was any talking. I hated the kid’s section that was in the back of the theatre, so I snuck closer into the adult area and sat in an empty dark row, then sunk down low so the psycho nurse/matron/woman in white would not see me. I caught the last half hour of Dracula, which wasn’t scary at all; it was actually kind of silly with its silent movie style school of acting.

After some cartoons, the lights dimmed again and Frankenstein began. From the very beginning I knew this movie was going to scare me in its plausibility of modern science creating a creature that turns into a monster beyond human control. I sank lower and lower into my seat as the laboratory scene started with its crackling sparks shooting from dipole to dipole, whizzing lights, ultra violet rays, and the sound of a raging electrical storm outside the castle. The cadaver was on the lab table and up and up it went into the open ceiling to meet the lightning bolts and crashing thunder that would spark life into the dead body. The table descended back to its starting place as Dr. Frankenstein threw off the white sheets, revealing a huge lumbering body with the monster’s face still wrapped in gauze. Suddenly the oversized hand of the creature reached up grasping for life as Victor yelled out deliriously, “It’s alive! It’s alive!” I cowered in anticipation of seeing his face revealed.

.

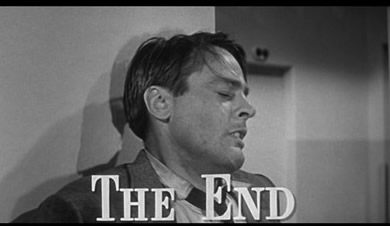

The Monster

And then a few scenes later, it happened. The laboratory door opened and the hulking monster loomed in the massive oak doorway with its back to us. Slowly the creature turned with its massive, strong arms slightly akimbo, jutting out of its sleeves of his too short torn black jacket. Suddenly the camera zoomed in on the three quick close-up shots on the dead expressionless face with its dull gray eyes and grimacing smile. When the creature groaned a piercing, death rattling GRRRR I jumped up, spilling my butter popcorn all over my lap as my theatre seat cushion made a big bang springing upright. That brought the matron storming down the aisle, chasing me as I ran past her to the brightly lit lobby and then out into a rainstorm.

Breathlessly I ran up 9th Street, crossing against the light at Fifth Avenue, careering from an auto turning left, stopping for a breath under the marquee of the RKO with its blinking yellow light bulbs that cast a deathly pall all over my face. As I dashed right onto Sixth Avenue I thought about how I was going to tell my mother why I had left the double feature early. So I ducked into the vestibule of the Ladies’ Entrance of Murphy’s Bar & Grill, which was right next to our vestibule since we lived above the bar. I was shivering as I waited for time to go by.

I must have waited a half hour when my mother coming down to check the afternoon mail and bring out the garbage, saw me huddling in the darkness. “What are you doing there? Is the movie over already?” I blurted out that I ran out because I got scared. “Oh silly boy, oh you silly boy, you should have just come up stairs. I don’t know why you go to those stupid movies, they scare you so.” I silently walked up stairs in shame behind my waddling mother, her hand on the rail to steady her lest she fall.

Tea and Sympathy

Mom toweled dried my hair and got me some dry clothes, then went back to getting dinner ready for us. Since my little bed was in the same front room of our brownstone across from my parent’s big double bed, I locked myself in our only bathroom to change. I was taking a bit longer than usual, which made my all-knowing mother yell out: “Whaddya doing in there? Stop playing with yourself!” I quickly pulled up my pants and nonchalantly sauntered over to the couch and watched some TV. It was late fall, it had gotten dark at 6:30 pm and Dad was still not home for dinner. Mom looked worried as I sat in guilty silence watching King Kong for the 5th time on Million Dollar Movie on Channel 9. “How many times you gonna watch that monkey movie? You want to have nightmares again?” Mom seemed anxious, so during the commercial I sat down next to her at the kitchen table and held her hand. After this unguarded moment, she shooed me away back to the couch. It was now 8pm and Dad was still not home. and he couldn’t call home since we didn’t have a telephone at that time and made all our calls from the corner Candy Store Telephone Booth. I could hear the steady rain rapping against our backyard facing windows.

From the hallway, I heard heavy, hard stumbling steps; keys fumbling. The door slowly opened and there was my father with his back to me as he turned around jerkily struggling to take his coat off. The sleeves seemed torn. “Tony where the hell, were you? I‘ve had dinner ready since 5pm. I was so worried…My God what happened?” My father stood there still, lumbering, towering over me as I looked up from the coach. “Josie, I was in a small car accident. I’m not hurt.” “Thank god you’re alive” my mother cried as she rushed to him and helped him take off his thoroughly soaked coat.

My father sank down on the floral print covered club chair and covered his face with his dirty, bruised hands and uttered a long, low sigh. He looked up at me, waving his hands for me to come over and sit on his knee. I was strangely hesitant to come over, but I gradually got on his lap and buried my head on his shoulder. He held me in his arms without saying a word. Mom came over and put a gauze bandage on a small gash on his forehead. “Dinner is ready.”

Dad’s Sedan

The following week, Dad took me to visit Nona grandmother, for Sunday dinner. My Italian grandmother lived in the Belmont Section of the Bronx. We drove over the Brooklyn Bridge, up the East Side Highway to the Major Deegan Expressway, down Fordham Road to Beaumont Avenue. Mom stayed home with my brother Michael, as she was getting big. I didn’t know how I felt a about having a new stranger come into the family especially if it was girl.

I kept sneaking a look at Dad to see if he was alright, his bandage slowly flapping a bit in the wind. He seemed ok but his face was strangely still. We ate upstairs at my Aunt Mary’s who made her famous meatballs with ziti slathered in a thick blood-brown tomato sauce. Uncle Nick always added 7-Up to his glass of CK Brand jug red wine and would give me indulgent sips. This was followed by a big bowl of braciole, loin lamb chops with lemon wedges, broccoli rabe and salad with a very tart wine vinegar dressing. Dad and I had stopped into Artuso’s beforehand, so we had cannoli for dessert while he went into parlor to watch the Giants playing at nearby Polo Grounds. Uncle Nick gave me a taste of his anisette laced strong black espresso, which gave me a curious buzz.

All of a sudden my father, closing the belt of his pants which he had unloosened after dinner, jumped up and said in his best wise guy accent, “Anthony, let’s blow this joint!” Quick kisses all around as we raced down the stairs to the car. But instead of continuing across Fordham Road, he made a sudden left turn onto The Grand Concourse, saw an open spot across from Krum’s Candy Store and glided the auto into a tight space. We dashed out of the car and he pulled me along the crowded street and up to a kiosk under the marquee of the grand, Loews Paradise Theatre.

“One Adult, One Child” and we were in. And wow what a place it was; an overwhelming, spectacular movie palace making the Avon Theatre look like our little TV set. Through big bronze doors you entered the three story lobby with a sweeping grand staircase and real goldfish splashing in the fountain. A beautiful young man dressed as smartly as any Roxy usher led us to our seats in this 4,000 seat Mecca. Inside was an Italian 16th century baroque garden fantasy with cypress trees, stuffed birds, and classical statues and busts lining the walls. The safety curtain was painted with a gated Venetian garden scene, which continued the garden effect around the auditorium when it was lowered.

Loews Paradise Today

“I know you like scary movies, you’re gonna love this one.” I began sinking in my seat when the theatre organ stopped playing, the lights dimmed, and the curtain opened to reveal the title of the movie, The Invasion of the Body Snatchers. Set in California, Bennell, a local doctor, finds a rash of patients accusing their loved ones of being impostors. He soon discovers that the townspeople are in fact being replaced by perfect physical duplicates, simulations grown from giant plantlike pods. As the movie neared its climax, I turned away from the screen. I looked up to the ceiling of the Loews Paradise where stars shone through a dark blue night sky with gossamer clouds wafting from left to right. It was like heaven up there, but hell here below as I could still hear the soundtrack as I watched the horror movie about human beings being taken over by aliens, transforming them into zombie like creatures with cold emotions and no feelings. I looked at my father to my right and shuddered. The final scene really jolted me as the hero screamed to people who don’t believe him – “Doctor, will you tell these fools I am not crazy? Listen to me, Please Listen to me. There not human! They already here! They are here! You’re next!”

Before the house lights could come up, my Dad, realizing it was getting late, grabbed my hand as we ran up the aisle almost knocking down the usher who was guarding the door and flashing his torch light in our faces. Outside, up on top of Loews Paradise, the clock with St. George was slaying the dragon and chiming six o’clock. It was raining yet again, so we scurried to the car. My dad sped down the Concourse, past the Cross Bronx Expressway and Mt. Eden Parkway as we left the Bronx behind us on our way home to Brooklyn. I nodded off in the car and I could feed my dad’s hand on mine as he drove down the East River Drive, with his other hand jauntily on the steering wheel. My Dad seemed like himself again. I was shivering since he liked to drive with the window open and the radio blaring. He must have been cold too since I could feel his hand trembling and shaking on top of mine.

Mom had Sunday night sandwiches for us. I went to bed at the usual 8:00 pm and quickly fell into a fitful sleep. In the middle of the night I woke up with a start with the words of the movie re-playing in my head – “Listen to me. There not human! They already here! They are here! You’re next!” My brother Michael was still asleep next to me. In the darkness I peered across the room at my father and mother lying side in their bed by side on their backs like two peas in a pod – Mom with her swollen belly covered by the chenille, Dad lying on top of the covers, his hand moving with a small sudden tremor, perhaps from a night chill. I got up and covered him up a bit with the white top sheet when he gave a short snort that made me run back to bed.

Mom, Dad and me

I woke up late on Monday morning and things were as usual: Mom quietly making me cereal, Dad already off to work, me playing a bit with my baby brother before I headed off to school; Sister Rose making me sit in the corner for being the class clown, after school a Lime Ricky at the candy store , hide and go seek with my neighbors Joey and Petey, homework in front of the TV, Dad coming home, dinner with all of us around the table, dessert with Mom, bed with my brother Michael hogging the blankets – an ordinary day, all in all, as if nothing had changed …

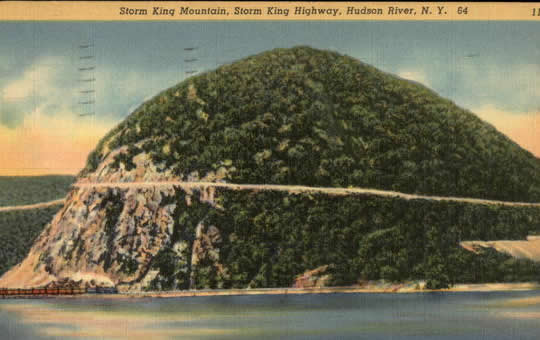

The following month I had a new baby sister and the following year we moved from Brooklyn to Newburgh, New York.

Note:

My father always said that the car accident triggered his Parkinson’s. He was a strong willed and determined kind of guy, who would not permit the disease to slow him down. In 1959 to early 1960’s he underwent three experimental operations to control his tremors and shaking. After those unsuccessful attempts, my father took up his own regimen and continued to work at Cel-U-Dex till the late 1970’s. He died in 1983.

(To be continued)